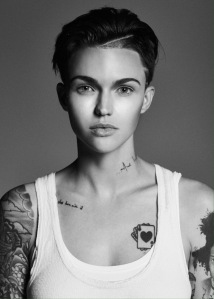

The young person sat in front of me is noticeably androgynous in a loose tunic, with elfin features, the sharp cheekbones of a male-model, and an overgrown pixie-cut. My assessment form demands a tick in the box, are they male or female? I wonder if they fall somewhere outside of this binary, if maybe they define themselves as genderqueer, or somewhere else on the gender spectrum. Maybe they don’t use any label for how they see themselves. I’d like think of myself as reasonably open-minded and something of an ally for LGBT rights and gender diversity, so I want to make an effort, to get it “right”. But I’m also conscious of causing offence – what if they do identify as male, will they be insulted by my asking? Maybe they’ve had a lifetime of being mislabelled as feminine. Will this break down our relationship before it’s even begun?

“What would you like me to put down for gender?”

(pause, confused expression) “Um…male”

“Okay… I only ask because some people identify as genders different from “male” or “female””

“Oh yeah… I know some people like that”

“Okay, what shall I put for your ethnicity?”

And so we move on.

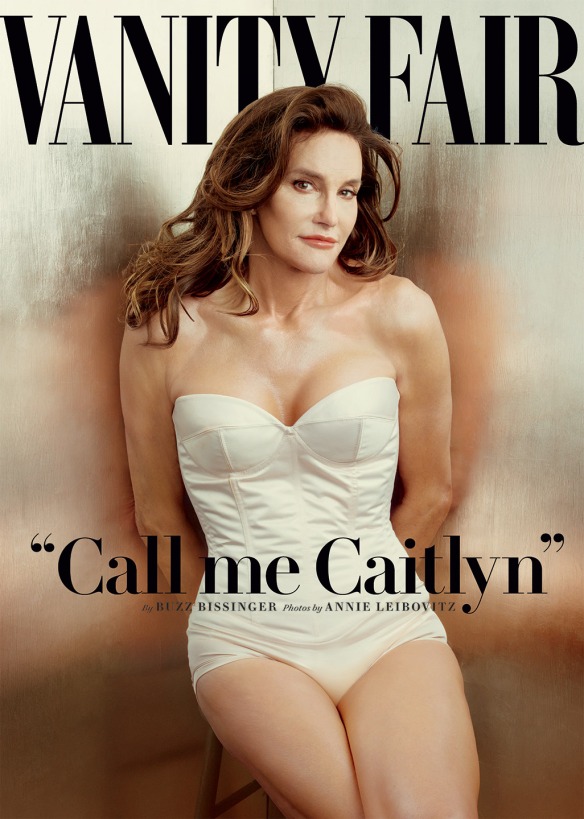

This encounter made me think about how I ask questions about demographics and diversity. In healthcare often the forms we use as restricted – used to generate statistics and leaving little room for greyer areas. But there are many aspects of personhood that aren’t immediately obvious. I have no difficulty asking someone their age, but somehow checking in with someone about issues such as gender and sexual orientation feels more difficult – my concern is that others will think I have made assumptions about them, “What makes you think I’m gay?”.

One way of making diversity questions less personal is to ask them routinely, even when the answer may appear “obvious”. Guesses at ethnicity and sexual orientation are also open to error without checking in (for example: someone who appears caucasian but is actually of mixed heritage). It is time-consuming to run through these kinds of questions but when I have the chance I do find it helpful. Most of the clients I work with have “majority” characteristics but they are rarely offended when I ask anyway. Often the form can be a starting point for these conversations “It’s something we ask everyone” and can reveal difference that isn’t immediately obvious in a relatively safe manner. Giving people assessment forms to complete themselves may also be another route, and including “other” boxes alongside diversity checklists. I also wonder, for those who sit in the majority groups, whether being asked the question provokes some thinking about diversity and brings a degree of normalisation.

NB – I don’t consider myself an expert on these topics, this is merely a reflection on my own experience. I recommend anyone interested in informing themselves about being sensitive and inclusive towards gender diverse individuals do some research – e.g. BPS, genderbread , Christine Richards.